Below you will find an essay I wrote for a course on Camus. As such, the style is different than my usual writing here on Substack. Nevertheless, I hope you enjoy it.

From human experience arises the phenomenon of the absurd, a divorce between our nostalgia for a rational world that we can truly know and the irritating irrationality of what we find. Faced with this tension, man often seeks a way out. One way out is through denying one of the premises: perhaps we don’t need to know, or perhaps the world is indeed rational. The other way out, of course, is to simply cease to live and thus escape absurdity by escaping life.

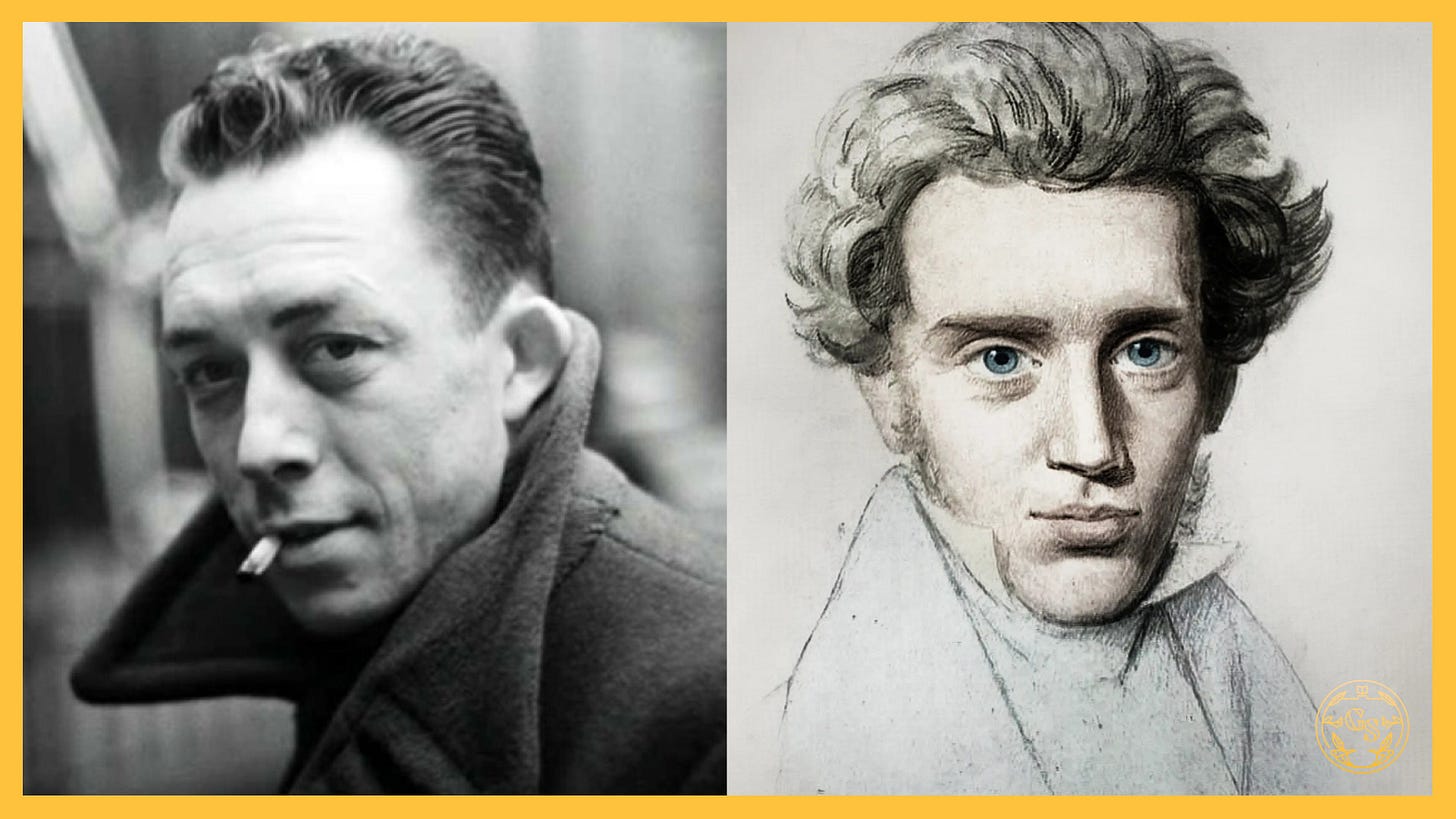

In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus eschews both of these options. The former he calls philosophical suicide; the latter, suicide. In so doing, he explores whether faith is an option for the absurd man - that is, the man who chooses to continue living amidst this tension. Camus, while not ruling out faith as a possibility for man in general, determines that faith cannot rise from the ashes of absurdity. But why? That is the question I will explore in this paper, namely, “What puts the Christian faith and the absurd man at odds?” To probe this question, I will focus primarily on Camus’s engagement with Soren Kierkegaard, a figure who acknowledges the absurdity of the world and yet makes a leap of faith.

What is the absurd?

Before we can fully appreciate what puts faith and absurdity at odds, we must ensure we have clear definitions for these concepts. Already above, I have referred to the absurd as a divorce. This is to use the very language of Camus in The Myth of Sisyphus. At the outset, Camus declares, “This divorce between man and his life, the actor and his setting, is properly the feeling of absurdity.” Again, later on, Camus writes, “The absurd is essentially a divorce. It lies in neither of the elements compared; it is born of their confrontation” (30).

In both of these quotations, Camus uses divorce to illustrate that the absurd arises from incongruity between two things. Described as, “man and his life” in the first, Camus later provides more clarity on what it is about man and his life that is incongruous or divorced. He writes, “But what is absurd is the confrontation of this irrational and the wild longing for clarity whose call echoes in the human heart” (21). Put simply, man desires to know things completely, yet the world in its irrationality deprives him of this certainty.

Now, it must be said that divorce, while a helpful term, leaves the possibility of a fatal misunderstanding. Divorce is often seen as the conclusion of a marriage. First there arises tension between the married individuals, then after tedious processes and paperwork, a conclusion is reached and a divorce is finalized. This is not the case with absurdity. Absurdity, for Camus, is not a conclusion one accepts about the world. Rather, it is the feeling of incongruity, of tension, of something not being right. Camus makes this plain in his introduction, wherein he writes, “But it is useful to note at the same time that the absurd, hitherto taken as a conclusion, is considered in this essay as a starting-point … There will be found here merely the description, the pure state, of an intellectual malady” (2). This could seem a small point, but it is essential because, for Camus, one must never accept the absurd. The absurd man does not resign himself to the absurdity of the world. He experiences it, and he makes this experience his criteria for all knowledge, but he does not rest on his laurels and say, “ah, yes, the world is absurd, and that is that. I shall now be on my jolly way having concluded that everything is absurd.” To do so would be to negate absurdity because it nullifies one of the two elements of absurdity. Once man stops striving to know and having a wild desire for clarity, he is no longer experiencing the absurd. As Camus writes, “the absurd has meaning only in so far as it is not agreed to” (31). This point must not be forgotten when we turn to his analysis of Kierkegaard.

Absurd Faith

When Camus delves the question of faith, he does so only within the context of absurdity. That is to say, faith that feels the full tension between man’s desire for clarity and the world’s answering irrational silence. Both the Calvinist and the rationalist are thus out of scope here. Any who, like the former, say that God can only be apprehended by those who are given a divine gift of faith aren’t relevant to Camus because they deny the first premise of absurdity, man’s desire for knowledges since only the regenerate could have this true desire to know God after having been gifted the desire and the faith by God. Likewise, the irrational world the absurd man knows and the ordered world the rationalist knows are too far apart for Camus to consider their faith relevant. Thus Camus writes, “It must be repeated that the reasoning developed in this essay leaves out altogether the most widespread spiritual attitude of our enlightened age: the one, based on the principle that all is reason, which aims to explain the world. It is natural to give a clear view of the world after accepting the idea that it must be clear” (41).

So what kind of faith is it that Camus has in mind? Primarily, it is the faith of Danish existentialist Soren Kierkegaard. For the purposes of this essay, a full analysis of Kierkegaard’s thought based on his own writings is out of scope. Indeed, whether Camus faithfully represents Kierkegaard’s thought is, for the time being, inconsequential. Within this essay, I will only describe Kierkegaard’s faith as Camus sees it and judge whether his rejection of it is consistent with his conception of what it is to be an absurd man.

Three elements of Kierkegaard’s faith are essential to Camus’ analysis. These are:

Accepting the absurd

Sacrificing the intellect

Taking a leap

I will evaluate these in turn. First, and perhaps most fatally for Camus, is Kierkegaard’s acceptance of the absurd. The reason Kierkegaard’s faith is relevant to Camus in the first place is because Kierkegaard, unlike many Christians, recognizes the absurdity of human experience. He does not see the Christian faith as perfectly rational in the sense that it gives an explanation of an orderly world in an orderly way. These explanations, as we’ve already noted, don’t interest Camus. Kierkegaard on the other hand is willing to stare biblical stories like the sacrifice of Isaac straight in the face and recognize that they don’t make sense. Indeed, all of human experience doesn’t make sense. The problem for Camus arises when Kierkegaard, in his estimation, says in effect, “yes, our lives are absurd, but that’s ok. In fact, God is absurd.” Just as the world is absurd, so too is God, and we must just accept that, so the faulty reasoning goes in Camus’s analysis. Camus writes, “[Kierkegaard] makes of the absurd the criterion of the other world, whereas it is simply a residue of the experience of this world” (38). This extrapolation from absurd experience to an absurd divinity is the illegal chess move of Kierkegaard in Camus’ estimation.

Camus also sees the absurd as fundamental, necessary even, but he doesn’t accept it or use it as a springboard for understanding the supernatural. He is concerned instead only with what he can experience first-hand. Speaking of the absurd man, he writes, “The absurd is his extreme tension, which he maintains constantly by solitary effort, for he knows that in that consciousness and in that day-to-day revolt he gives proof of his only truth, which is defiance” (55). This quote illustrates not only that absurdity must be maintained at all times, but also that, in so doing, one must never come to accept absurdity. Defiance and revolt must persist. Kierkegaard too knows the absurd, but he steps off the hamster wheel of wanting and failing to know and instead deems that this absurdity can teach him something about God. Absurdity must run all the way to the top, all the way to an absurd God.

The second and third points are intimately related to the first. Nevertheless, they have particular nuances which merit them standing on their own. Regarding the sacrifice of the intellect, this occurs as soon as one accepts the absurd. Once more, the absurd arises out of two things, a desire for certainty and the irrationality of the world. Accepting the absurd is, for Camus, rejecting the first element: a desire for certainty. This leaves an imbalance and turns its back on the experience that got the absurd man this far. If he only knew things previously through this tension, he cannot trust any move which resolves this tension because it takes away the very experience of the absurd which hitherto has been his only sage. For Camus, this amounts to sacrificing one’s intellect. Here it is important to recognize that Camus grounds his desire for certainty in the fact that we do have an intellect. Our desire for certainty, therefore, is not baseless. It goes unfulfilled, but the key here is that we come so close to knowing. Camus writes, “But if I recognize the limits of the reason, I do not therefore negate it, recognizing its relative powers. I merely want to remain in this middle path where the intelligence can remain clear” (40).

Camus gives the example of scientific knowledge to elucidate this. For the first few steps, it appears we really can know, which only serves to fuel our desire for certainty. He writes, “So that science that was to teach me everything ends up in a hypothesis, that lucidity founders in metaphor, that uncertainty is resolved in a work of art” (20). Kierkegaard, however, in accepting the absurd effectively denounces the intellect. He agrees with Camus that it can’t get us as far as we want, but unlike Camus, he’s willing to leave it behind.

This forsaking of the intellect is what fuels the final element of Kierkegaardian faith: the leap. Kierkegaard has experienced the absurd, he’s felt the dizzying heights of nearly knowing yet not knowing, and instead of standing on the edge, he leaps. And what is this leap? It is a leap to allying oneself with a God that he cannot understand, a God that is absurd. It is a leap that moves him from the way he’s known thus far, namely, through the experience of the absurd, to a new way of knowing that takes the absurd now as a conclusion and rides it straight to the heavens.

Camus’s response to Kierkegaardian faith

In outlining the elements of Kierkegaard’s faith, I have already established many of Camus’s objections. Where Kierkegaard accepts the absurd, Camus demands that we never do such a thing, living constantly in the tension of the absurd. While Kierkegaard sacrifices the intellect by denying that we should maintain a nostalgia for understanding, Camus argues we must never give up. Finally, when Kierkegaard leaps, Camus orders the rest of us to keep our feet firmly planted on the edge. In other words, everything that defines Kierkegaard’s faith, in Camus’s reckoning, is wrong. Kierkegaard thinks he can use the ingredients of absurdity to produce a theistic dish while Camus insists that these ingredients, without illicit additions or subtractions, simply can’t yield faith. This is what puts them at odds.

Is this no more than a “he said/he said?” Is it simply a matter of preference, Camus insisting on his way and Kierkegaard doing likewise? In some ways, the answers to these questions are yes. Neither man seems to believe that anyone can prove whether God exists or does not exist. Thus, the question for Camus is not so much whether Kierkegaard is right or wrong in his conclusion. He seems to be agnostic on this point. Instead, Camus wants to know whether Kierkegaard is consistent. In the end, this question revolves around whether the experience of the absurd can lead to belief in God without forsaking its principles. Upon deeper analysis, the question shows itself more encompassing, bringing into consideration not only whether absurdity can generate belief in God, but whether it can generate new knowledge, specifically of things outside oneself and one’s direct experience, at all.

Absurdity as the fount of nothing

When Kierkegaard rejects nostalgia for certainty and accepts the idea of an absurd God, he opens new horizons to his worldview with a new assertion: God exists. At least, that seems to be Camus’s understanding and his main gripe. After all, the absurd man knows only one thing - his absurd experience of life. The rest he desires to know with certainty and yet he can’t. Not only does this not lead to God, it doesn’t lead to anything new, propositionally speaking.

It’s important to note that throughout Camus’s work, while he proposes many outcomes of absurdity, such as revolt, freedom, and passion, he doesn’t posit new knowledge in the form of a worldview or moral code. The absurd man does not learn new things through his experience of the absurd. Rather, he develops new attitudes and actions from his experience of the absurd.

Camus writes, “Let me repeat that these images do not propose moral codes and involve no judgments: they are sketches. They merely represent a style of life” (90). So, what does Camus know? Very little. He writes, “Of whom and of what indeed can I say: ‘I know that!’ This heart within me I can feel, and I judge that it exists. This world I can touch, and I likewise judge that it exists. There ends all my knowledge and the rest is construction” (19).

Thus, we can conclude that, to the extent the leap of faith involves one acquiring new knowledge about God, it betrays its principles. It is this knowledge of God which extends beyond absurd experience that puts the absurd man and faith at odds. The absurd man, committed to knowing nothing but absurdity, cannot now add additional, fundamental truths to his understanding of the world. Camus is right, therefore, when he says that belief in God, wherever it comes from, does not come from the experience of the absurd, carried out consistently.

Question 1: Is faith knowledge?

Before the matter is settled, there are important assumptions to interrogate. First, is Kierkegaard’s faith a matter of the intellect? Here, perhaps Camus doesn’t delve Kierkegaard’s sacrifice of the intellect far enough. If Kierkegaard truly has sacrificed the intellect, then it may be that faith is more a matter of disposition than of mind for him. Faith is thus a choice to say yes to the absurd God, not to establish his existence from a set of reasonable conclusions. Construed along these lines, faith in God, especially a God that doesn’t require one to forsake the notion that the world is irrational, is not altogether different from something like freedom or revolt. If absurdity can be generative of freedom, it could be generative of the disposition of faith, if not the belief of faith. After all, Camus cannot justify the abstract idea that freedom exists, only that he is free. He writes, “In order to remain faithful to the method, I have nothing to do with the problem of metaphysical liberty. Knowing whether or not man is free doesn’t interest me. I can only experience my own freedom” (56). In a similar way, absurd faith could posit that one exists in a theistic world, without saying much about the nature of the existence of a God.

In this first point, I have raised the possibility that Kierkegaard’s faith is not a matter of adding new knowledge but rather is a disposition. As such, it does not fall prey to the non-generativity of absurdity. However, it is not yet clear from whence faith derives. The second question will narrow in on the source of faith by looking at desire.

Question 2: What is the role of desire?

At the end of his first section on Kierkegaard, Camus anticipates how the Dane would respond to his arguments. He writes for him, “If man had no eternal consciousness, if, at the bottom of everything, there were merely a wild, seething force producing everything, both large and trifling, in the storm of dark passions, if the bottomless void that nothing can fill underlay all things, what would life be but despair?” (41). Camus is not moved by this. He simply responds, “Seeking what is true is not seeking what is desirable” (41).

Here, however, is where we may find fertile ground. Camus’s recipe for absurdity involves our nostalgia for certainty and the irrationality of the world. In doing so, he makes desire a core criteria for human experience. If human experience is characterized by absurdity, desire is a fundamental aspect of what shapes our absurd lives. What is a nostalgia for certainty if not a desire? Therefore, desire is one way in which the absurd man attempts to make sense of the world.

At this point, Camus and Kierkegaard can agree. Human desire fundamentally shapes human experience. Kierkegaard, however, introduces desires other than certainty: freedom from despair and the infinite. What makes the absurd man subjugate all desires other than that for truth? Is it possible to desire truth but desire other things even more while still being absurd?

At the surface, it seems possible that Kierkegaard could maintain absurdity while simultaneously desiring peace and acting in accordance with this. As Camus will attest, being an absurd man doesn’t require one to be miserable. It simply requires that you maintain the tension, and finding peace in God does not by definition negate this if that peace was not reached by positing new, illicit knowledge.

Possibly anticipating this, Camus not only asserts that desire and truth are different, but he goes one step further by casting doubt over whether Kierkegaard’s pursuit of peace is effective. He argues that Kierkegaard’s leap results in him effectively mutilating himself, writing, “I do not want to suggest anything here, but how can one fail to read in his works the signs of an almost intentional mutilation of the soul to balance the mutilation accepted in regard to the absurd?” (39). The first response to this, of course, is that whether or not Camus intends to suggest anything here, he does, and his attempt to downplay that belies the uncomfortable truth that none of us can access whether or not this did in fact work for Kierkegaard.

This brings us back to a question regarding both of the above points. If it is the case that man can fulfill his desire for peace through taking a leap of faith, and that leap of faith does not add new knowledge but just a novel application of the feeling of certainty to a disposition of faith, have any principles been violated? It seems possible that such a man of faith could still experience the dizzying heights of uncertainty amidst an irrational world, even if that world involves God. While Camus insists Kierkegaard has accepted the absurd by introducing an absurd God, it is not clear that this is the case. Prima facie, there’s nothing about a disposition of faith that stops one from desiring certainty, thus maintaining the requisite tension. Kierkegaard may have no more certainty about this God than anything else. Therefore, he is not eschewing the absurd, he is merely applying it to a new domain and he is doing so in alignment with his desires, which are fundamental to absurdity.

Question 3: Is the “supernatural” fundamentally different?

This brings us to an essential point in Camus’s argument against absurd theism. For Camus, there is a harsh distinction between the natural and the supernatural, and to carry the experience of one to the other is a philosophical sleight of hand, at best. When discussing how Kierkegaard finds hope in death, he writes, “But even if fellow-feeling inclines one toward that attitude, still it must be said that excess justifies nothing. That transcends, as the saying goes, the human scale; therefore it is superhuman. But this ‘therefore’ is superfluous” (40). Here, Camus discerns a leap arising from a desire transcending the human scale and arriving at a being existing that transcends the human scale, God.

Interestingly, Camus fails to recognize that he does something radically similar. As we have noted, Camus is driven by his fundamental desire to know things fully, with certainty, yet he cannot find this certainty in anything outside himself. In other words, he desires a mode of knowing that transcends his scale, yet he lives as though it does in fact exist by constantly pursuing it. The parallel to faith is striking. Kierkegaard lives with a desire for God, or in other terms, peace and the infinite. However, these things elude him, so he takes a leap, believing that the things he desires correspond to reality. Camus might respond that in his case, searching for certainty is not a leap because he keeps the tension. But what is faith if not tension and a hope for things unseen?

The only thing that keeps Kierkegaard’s faith different is that it corresponds to something we traditionally conceive of as supernatural. In this way, it is off limits when we assume that any “supernatural” elements of human experience must be proved since they are, as it were, additions to basic human experience. However, this seems to be a tenuous claim. The experience of the divine seems just as common, if not more common, than the experience of the absurd, and it’s not necessarily the case that those who experience the divine have “added” a supernatural belief to their baseline worldview. Instead, their baseline worldview simply included space for the divine.

In other words, while Camus maintains a strong distinction between the supernatural and the natural, others see a continuity here. For Kierkegaard, the experience of the natural world organically includes things that others would deem supernatural or things that help us understand the supernatural. There is no sleight of hand here because the two things - natural and the supernatural - correspond to one another in such a way that our experience of the former can shape our understanding of the latter.

Summary: How the absurd man can attain and maintain faith

Camus describes his interaction with religion by saying, “Our aim is to shed light upon the step taken by the mind when, starting from a philosophy of the world’s lack of meaning, it ends up by finding a meaning and depth in it” (42). And for Camus, the answer is clear: “The absurd, which is the metaphysical state of the conscious man, does not lead to God” (40).

Camus is right if being an absurd man requires that one restricts the only meaningful data points for consideration to the irrationality of the world and our desire for certainty, and if by God, he means an intellectual conclusion that God exists. If these are the only two things that constitute the absurd man’s experience and all else is irrelevant, then this doesn’t lead to the conclusion: therefore, God. However, one of the important discoveries of this paper is that this is not due to anything special in the nature of the claim of God’s existence. It is merely due to the fact absurdity, so tightly construed, is not generative of any new beliefs corresponding to the world outside oneself because it insists on maintaining man’s inability to know with certainty as one of its two foundational premises. This, therefore, makes the statement that absurdity doesn’t lead to God a bit lackluster.

However, if we are able to construe absurdity as a foundational experience of man while rejecting the notion that belief in God is an intellectual conclusion or granting that making a human desire, certainty, constitutive of human experience opens up the possibility of other desires being equally important, such as faith, then we are able to see how even an absurd man can be a man of faith. I will explain these in turn.

First, if faith is not an intellectual conclusion, but rather a state, choice, or disposition, it does not fall prey to Camus’s tight reasoning. For example, absurdity is generative of the feeling of revolt, freedom, and passion. Camus rights, “Knowing whether or not man is free doesn’t interest me. I can only experience my own freedom” (56). In the same way, the absurd man of faith could potentially say, “Knowing whether or not God exists doesn’t interest me. I can only experience my faith.” Kierkegaard chooses faith as a consequence of absurdity because it is one of the two options at hand: despair or faith. Camus rejects faith as an option, but that’s because he insists we cannot know the supernatural. However, we can know faith in the same way we know despair - as a phenomenon, and nothing about the tight logic of absurdity keeps us from phenomena, only conclusions.

Second, if absurdity is grounded in human desire, namely for certainty, and we can extrapolate from this that human desire grounds human experience, then we can find faith in yet another way. In this, we can say that faith is as fundamental of a human desire as certainty. In fact, it might better explain the experience of the absurd because the absurd, while grounded in a quest for certainty, is a constant reminder that certainty is impossible in an irrational world. Faith, however, is not impossible in an irrational world. True, it may be difficult. As Kierkegaard insists, it may be a faith that doesn’t flinch at the sacrifice of Isaac, but it is faith nonetheless. Because this form of faith can sit at the excruciating foot of the cross, it need not negate the fundamental tension of the absurd. The absurd man can desire certainty, experience the irrational, and hold them in tension with a faith that does not tidily explain the world, but allows a man to push forward nonetheless.

The questions that remain

This inquiry began with the question of what puts the absurd man and faith at odds. Quickly, we discovered that the idea of the non-generativity of absurdity is a more fundamental problem within which the problem of faith amidst absurdity resides. To examine Camus’s argument, I have put forward a case that a type of faith that is not a conclusion could pass his rigorous logic.

However, it must be admitted that this raises new questions. First, there is the matter of whether a faith in God that does not posit that God exists is both logically coherent and expressive of what Camus imagines as Kierkegaard’s faith. In Christian theology, faith is not generally a disposition that latches onto nothing. Christians do not speak of “faith in faith” but “faith in God.” While I have attempted to show that the experience of a theistic world could be basic to human experience and not additional,, it is unlikely that those who do not believe in God would grant that experiences that appear to be congruent with a theistic world indeed establish that God exists. Furthermore, it is difficult to ascertain the extent to which the type of faith I’ve laid out corresponds to Kierkegaard’s faith since, for the purposes of this essay, I’ve limited myself to Camus’s representation of his faith. In many ways, the case laid out benefitted from the fact that Kierkegaard was given little space to speak for himself in The Myth of Sisyphus allowing me to flesh out his faith in a way that navigated the logical landmines of absurdity. It is entirely possible that if the great Danish thinker were able to read this he may object to much of what I’ve written.

Moving forward, the questions for inquiry involve allowing Kierkegaard’s own writings to respond to the vision of faith I have set forth, delving further into the coherence of this faith, and perhaps above all, continuing to explore what it means for absurdity to not be generative of conclusions outside ourselves. While I have shown that faith can be amended to this final requirement, it may be that we can turn many would-be conclusions into dispositions. Is this then not falling prey to Husserl’s phenomenology, the flip side of Camus’s examples of philosophical suicide? While it would seem that the faith I’ve described aligns with Camus’s account of freedom, it is possible that this points more to a flaw in Camus’s acceptance of freedom than it does to the logical consistency of turning conclusions like “freedom exists” into phenomena such as “I experience life as one who is free” while maintaining that we are seeking certainty.

With these questions, and surely others this essay could raise, I rest assured that the absurd reader is left precisely where he is most at home: knowing in tantalizing part, yet grasping at an elusive certainty.