“Why did you study theology?” It’s a question I get fairly often, especially from people who know me from work and are trying to square a career in marketing with years spent studying dusty old texts. College isn’t cheap, and the ROI on a theology degree—or a Master’s in Liberal Arts to make matters more dire—isn’t great.

I’ve toyed with different answers to that question over the years, all of which have a hint of truth but lack the full picture. The best I can come up with these days is that I spend my life in search of great conversations and compelling conversation partners. In theology, I’ve gotten to explore the biggest questions around a table crowded with conversation partners that stay with us in their words down through the centuries.

As is the case in many crowded conversations, there are endless side conversations and no shortage of interesting characters. Some you’ll jive with, others you’ll bristle at, many you’ll make small talk with and move on. Occasionally, though, you find a conversation partner that envelops your attention. One upon whose every word you hang.

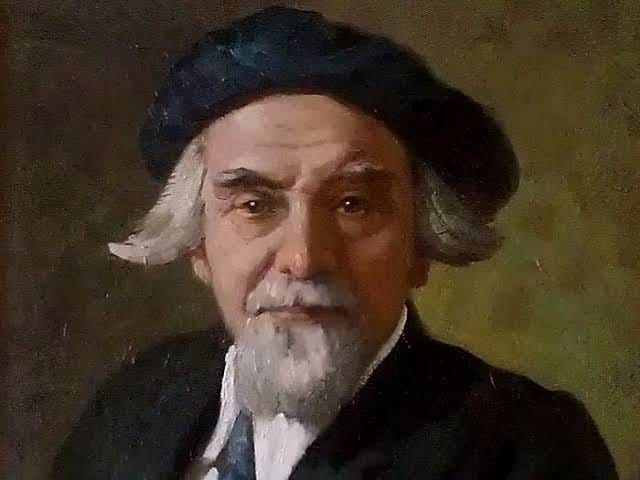

Recently, I’ve come across such a figure in Nikolai Berdyaev.

Background on Berdyaev

Berdyaev is not exactly a household name in American theological circles. Even with the current wave of converts to Eastern Orthodoxy, many will not know of him. If one is feeling edgy and wants to dabble in Russian theology, they’re more likely to come across his peer, Sergei Bulgakov.

Suffice to say, don’t feel bad if you haven’t heard of him (but you’re welcome for changing that).

There’s much that can and should be said of him, but odds are you clicked on this article for the “beauty” portion of the title rather than the “Berdyaev” portion, so I’ll keep it short.

Nikolai Berdyaev was born in 1874 to an Aristocratic family in Russia. Like many young men of his time, he became interested in Marxism. However, he soon became disillusioned with it, and he did so at precisely the wrong time. By the time he was questioning mainstream Marxism, doing so was the type of thing to get you exiled, which is precisely what happened to him.

Berdyaev traded in his Marxism for Russian Orthodox Christianity with an existential flair. He had a complicated relationship with the church, often deriding clericalism, and yet, his account of why he was Orthodox should be required reading for all considering swimming the Bosphorus.

His philosophy defies systematization, but is often characterized by freedom, creativity, and man as both divine and human. The second of these brings us to our topic today.

Berdyaev on Beauty

I like to underline and make notes in my books. I burned through a pen reading a single chapter of Berdyaev on beauty. You might forgive me when you realize the following are the opening lines:

Beauty is a characteristic of the highest qualitative state of being, of the highest attainment of existence; it is not a separate side of existence. It may be said that beauty is not only an aesthetic category but a metaphysical category also. If anything is perceived and accepted by man integrally, as a whole, that precisely is beauty.1

Three lines in, you realize you might want to be more sparing in your underlines, only to run into this, “Beauty is the final goal of the life of the world and of man … All beauty in the world is either a memory of paradise or a prophecy of the transfigured world.”2

The insight/word ratio does not slow down. In a single chapter, he lays out a compelling theory of beauty that makes even the Stoic want to sing.

In what follows, I’ll try to sketch a few of his key ideas to whet your appetite.

Beauty and prettiness

Today, we make one of two mistakes when it comes to beauty. Like a pendulum, we swing back and forth from a reduction of beauty to prettiness or a replacement of beauty with sentimentality. Berdyaev eschews both.

He writes, “Prettiness is fraudulent beauty. It relates to the phenomenal only; in beauty, on the other hand, there is a noumenal principle.”3

Now, Berdyaev isn’t saying that beauty is unrelated to appearances. That would be swinging the pendulum too far, but he is saying that it’s more than what meets the eye. Beauty must have internal and external harmony. When it has only the latter, it can be weaponized and used to deceive. In such cases, beauty “breaks away from the source of light.”4 When beauty abandons the good, it gives way not to a culture of creativity, but to one of passivity. For Berdyaev, this is aestheticism: When one cares about prettiness but not beauty.

Aesthetes detach beauty from truth and goodness, but by doing so, they rob beauty of its dynamism, for beauty is meant to transfigure the world, not just be gazed upon by those who care nothing for its true power. Berdyaev labels Nietzche an aesthete and writes, “It is intolerable that anyone should adopt an attitude of hostility towards the realization of greater equity in social life on the ground that in the unjust social regime of the past there was more beauty.”5 Without getting too far afield, I worry this happens with many zealous converts today who want all the trappings of tradition without recognizing the proper end of it. We become aesthetes of religion, admiring the externals that are dead without their inner life.

The subjective and objective

Related to the tension between beauty and prettiness is the classic question of whether beauty is subjective or objective. In other words, is beauty in the eyes of the beholder?

The answer is complicated.

The first reason for this is that Berdyaev thinks it’s the wrong question to ask because it often assumes the two options are that beauty is either a subjective illusion or its an object thing out there in the world apart from us. Both are wrong.

For Berdyaev, beauty is subjective, but not in the sense that it’s an illusion. He writes, “To say that beauty is subjective is also to say that it is real, for reality is to be found in subjectivity—in that existence which is still full of the primordial flame of life; not in objectivized being in which the fire of life has cooled down.”6

Naturally, I underlined that sentence as well.

This answer relates back to Berdyaev’s fierce love for the human person. The goods of life are not found outside and above humanity, but within it. So of course beauty is found in subjectivity. This insistence upon personalism is not to relegate God to irrelevance. In fact, it’s only true because true humanity is divine humanity.

To be human, for Berdyaev, is to actualize the divine. It is dynamic.

So too is beauty. Beauty is a grasping at the infinite in the midst of the finite. The infinite, we could say, corresponds to the objective, something beyond us, or at least seemingly so. The finite is something closer to home.

Berdyaev relates this to two forms of art: Classical and Romantic.

Classical art focuses on perfecting the form of the finite. Think of Michelangelo’s David. Romantic art does not seek to capture the finite but instead gestures at the infinite. Both are beauty for Berdyaev, and even more importantly, both need each other. To summarize, Berdyaev writes, “Beauty is linked with form, but beauty is also linked with the creative force of life, with aspiration towards infinity.”7

The Good and the Bad News about Beauty

If someone ever says to you, “do you want the good news or the bad news first?” you choose the bad news. Unless you’re a glutton for punishment.

Since I don’t hate you, I’ll give you the bad news first.

The bad news is this: It was getting hard for man to create beauty in Berdyaev’s time, and it has only gotten worse since.

Take these lines for an example:

The immediate sense of the beauty of the cosmos is weakened and beginning to give way, for there is no longer any cosmos. It has been destroyed by the physical sciences and by the power of technical knowledge of the human soul to-day. The machine is being placed between man and nature … Man is losing, as it were, the remnants of his memory of paradise. He is moving forward into a night in which no form is to be seen, but only the shining of stars. Here we come into touch with the end.8

That was in the 1940’s. You know, before people had ever dreamed of us forgetting how to read because we spend all day glued to glowing screens that act as intravenous streams of dopamine to lull ourselves into a self-imposed stupor.

For many, the only thing shining in the night is the next TikTok, not the god-forsaken, unseen stars beyond our ceilings.

Sorry to be the harbinger of doom, but if beauty was in danger then, the stakes today are that much higher.

Aren’t you glad you chose the bad news first?

Onto the good news: Berdyaev still thinks Dostoevsky was right, beauty will save the world.

Why? Because it has to, our faith demands it. The Christian must insist that goodness wins in the end, and the end of goodness for Berdyaev is beauty. When goodness triumphs over evil, when we go beyond good and evil, what are we left with but beauty? Reality itself, vindicated as truth and filled in every corner with the good is simply beauty. Beauty will win because it is what is real. Evil, ugliness, falsity are but parasites. Dark as the night may be, these parasites have no life of their own.

If that’s the answer to the why question, the brass tax comes with the how. For signs of life, Berdyaev points to an unlikely place. He does not look to his peers in the Russian Silver Age. He does not turn to the poetry, prose, or paintings of his time, great as they all were and deserving of the title beauty. Instead, in the onslaught of the machine, Berdyaev puts his hope in the liturgy.

He writes, “Among the dissolving forms of the world the worship of the Church possesses the greatest stability, and, as in time past, its beauty powerfully affects the emotional life of man.”9

For beauty to save the world, it must arise from the bosom of the Church. When it does, transfiguration becomes possible. In the worship of the Church, beauty, truth, and goodness unite to raise up the world, to transfigure it such that the divine pervades the human, and God’s will for the world is made manifest.

May it be so.

Nikolai Berdyaev, The Divine and the Human, trans. R. M. French, (Philmont, NY: Semantron Press, 2009), 139.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid, 140.

ibid, 140.

ibid, 142.

ibid, 143.

ibid, 146.

ibid, 146.

The modern world, in its relentless march toward efficiency, has made beauty a casualty. The machine, Berdyaev warns, has inserted itself between man and the cosmos, severing the last fragile threads of our memory of paradise. We no longer see the world as a theophany, as a reflection of God’s glory, we see it as raw material, as data to be processed, as a problem to be solved. The stars, once symbols of the infinite, are now obscured by the glow of screens, and the human soul, once capable of trembling before the sublime, has been anesthetized by the endless scroll of digital distraction.

And yet, here is the paradox: Berdyaev doesn’t surrender to despair. He clings, with almost reckless hope, to the belief that beauty must triumph, because evil is ultimately parasitic. Ugliness has no substance. It is a corruption, a negation. True beauty, like truth, cannot be destroyed, only forgotten, only obscured. And so, in the midst of the machine’s dominion, he turns to the one place where beauty still burns with undiminished fire: the liturgy.

One wonders what Berdyaev would make of our present moment, where even the liturgy is often reduced to a battleground of ideologies, where traditionalists and progressists argue over aesthetics while the world outside grows ever more alienated from the very idea of the sacred. Would he still believe beauty could save us? Or would he revise his claim, whispering instead that beauty must save us… because if it does not, nothing will?

Perhaps the answer lies in his insistence that beauty is not merely objective or subjective, but real. Real in the way that love is real, in the way that suffering is real, in the way that God is real. It is not an idea to be debated but a force to be encountered. And if the modern world has made that encounter harder, it has not made it impossible.

The stars still shine, even if we no longer look up. The liturgy still echoes, even if we no longer listen. And beauty, though exiled, has not yet abandoned us. It waits, like the return of Christ, like the resurrection of the dead, for the moment when we are ready to see it again.

My students are doing final papers on beauty. They were having a debate in class about their ideas to get things flowing. We were struggling with the concept of the beauty being the good, but some deadly animals (bad) being beautiful to look at and being created good by God. One student suggested that if they are doing what God made them to do, they are beautiful. It was amazing; he didn't know it but he was weaving beauty into theosis. To willingly cooperate with God is beautiful.

I also really like this quote from a beautiful book called Winter's Grace by K. William Kautz: “That’s what faith is… it is knowing in the darkness that a loving God has a plan that’s better than any we could ever imagine. A sovereign God adores us, and for this reason the ending of our stories will be beautiful.” Its a very short book and an easy read. Highly recommend.