“When, still before dawn, the body of the elder, prepared for burial, was placed in the coffin and carried out to the front room, the former reception room, a question arose among those attending the coffin: should they open the windows in the room? But the question, uttered cursorily and casually by someone, went unanswered and almost unnoticed—unless it was noticed, and even then privately, by some of those present, only in the sense that to expect to corruption and the odor of corruption from the body of such a deceased was a perfect absurdity, even deserving of pity (if not laughter) with regard to the thoughtlessness and little faith of the one who had uttered the question.”1

The mark of a great book is, in part, its uncanny ability to follow you long after you put it down. Resigned though it may be to a life of beautifying your bookshelves, a great book is never tied down. It travels with you, whispering in your ears even as you read other, lesser books.

The Brothers Karamazov is one of those books. Some books you know within the first chapter that it is a great book. Others you don’t know until later in the story. And then there are others, like Dostoevsky’s masterpiece, that you don’t truly appreciate until you find yourself returning to it long after you read the final words. That’s how it was for me. I confess, I didn’t much like the book while I was first reading it. Typing out each of those appositives packed into two sentences reminded me of my initial reticence.

And yet, I can’t help but find myself returning to it in my thoughts as I turn over the lingering questions. Perhaps no scene is more puzzling to me, more intriguing, than the death of Elder Zosima (insert retroactive spoiler alert).

Alyosha and the Elder

To make sense of this we must understand the role Elder Zosima played in the life of the book’s hero, Alyosha. When Dostoevsky first introduces Alyosha to the reader, he takes care to note that he was not a fanatic nor even a mystic. While he is, of the three brothers, the sole one committed deeply to the Orthodox faith, it is not because of some unique, inherent religious quality that separates him from the rest of common men.

No, there were two things that made Alyosha follow this path: his love of mankind and the example of the elder. Dostoesvsky writes:

“He was simply an early lover of mankind, and if he threw himself into the monastery path, it was only because it alone struck him at the time and presented him, so to speak, with an ideal way out for his soul struggling from the darkness of worldly wickedness towards the light of love. And this path struck him only because on it at that time he met a remarkable being, in his opinion, our famous monastery elder Zosima, to whom he became attached with all the ardent love of his unquenchable heart.”2

Within the beating heart of Alyosha’s faith is the Elder Zosima.

If you’re not familiar with Orthodox elders, they are monks, but not any monks. Dostoevsky writes, “What, then, is an elder? An elder is one who takes your soul, your will into his soul and into his will. Having chosen an elder, you renounce your will and give it to him under total obedience and with total self-renunciation.”3

This relationship is even deeper and requires greater obedience than what one finds in a normal monastic vow. For Alyosha to take Zosima as his elder is to hand his whole self over to the elder.

Throughout the early parts of the book, we see the holiness of Zosima on display, and in Part Two, Book Six, we get multiple chapters devoted to the life and teachings of this great monk.

Between Alyosha’s love for him and his evident holiness, what happens at the start of Book Seven all the more troubling.

Instead of his dead body giving off the expected smell of saintliness, it begins to reek. What the people wanted to ignore becomes so overwhelmingly apparent that they begin to question whether they ever truly knew the man.

The odor of corruption

At the time that Dostoevsky was writing his book, there was a belief, if not official certainly held by many of the faithful, that one of the marks of a saint is that his or her body does not corrupt. This persists through the present day, where, in both Catholic and Orthodox churches, you’ll find incorrupt bodies of saints on display for the faithful to venerate.

This incorruption is not just the visible quality of a body not decaying. Critically for the story, it is olfactory as well. The body of a true saint, so the theory goes, will not emit the foul odor that commonly comes with death. Some saints’ bodies are even said to give off a sweet smell at the time of death.

For Elder Zosima, this was not to be. Before even a day had gone by, the whole monastery, indeed the whole town, was thrown into disarray due to the undeniable odor of corruption that filled the room where his coffin laid.

The unbelievers, the narrator tells us, were delighted. Even more so were some of the believers who took sick joy in seeing the downfall of a righteous man. But for Alyosha, this was a crisis of faith. The elder whom he loved was now being mocked, and people were openly questioning whether his holiness in life was not being shown to be a scam by his corruption in death.

This comes to a crescendo when Father Paissy sees Alyosha rushing away from the monastery in the aftermath.

“Where are you hurrying to? The bell is ringing for the service,” he asked again, but Alyosha once more gave no answer.

“Or are you leaving the hermitage? Without permission? Without a blessing?”

Alyosha suddenly gave a twisted smile, raised his eyes strangely, very strangely, to the inquiring father, the one to whom, at his death, his former guide, the former master of his heart and mind, his beloved elder, had entrusted him, and suddenly, still without answering, waved his hand as if he cared nothing even about respect, and with quick steps walked towards the gates of the hermitage.”4

Why does his body smell?

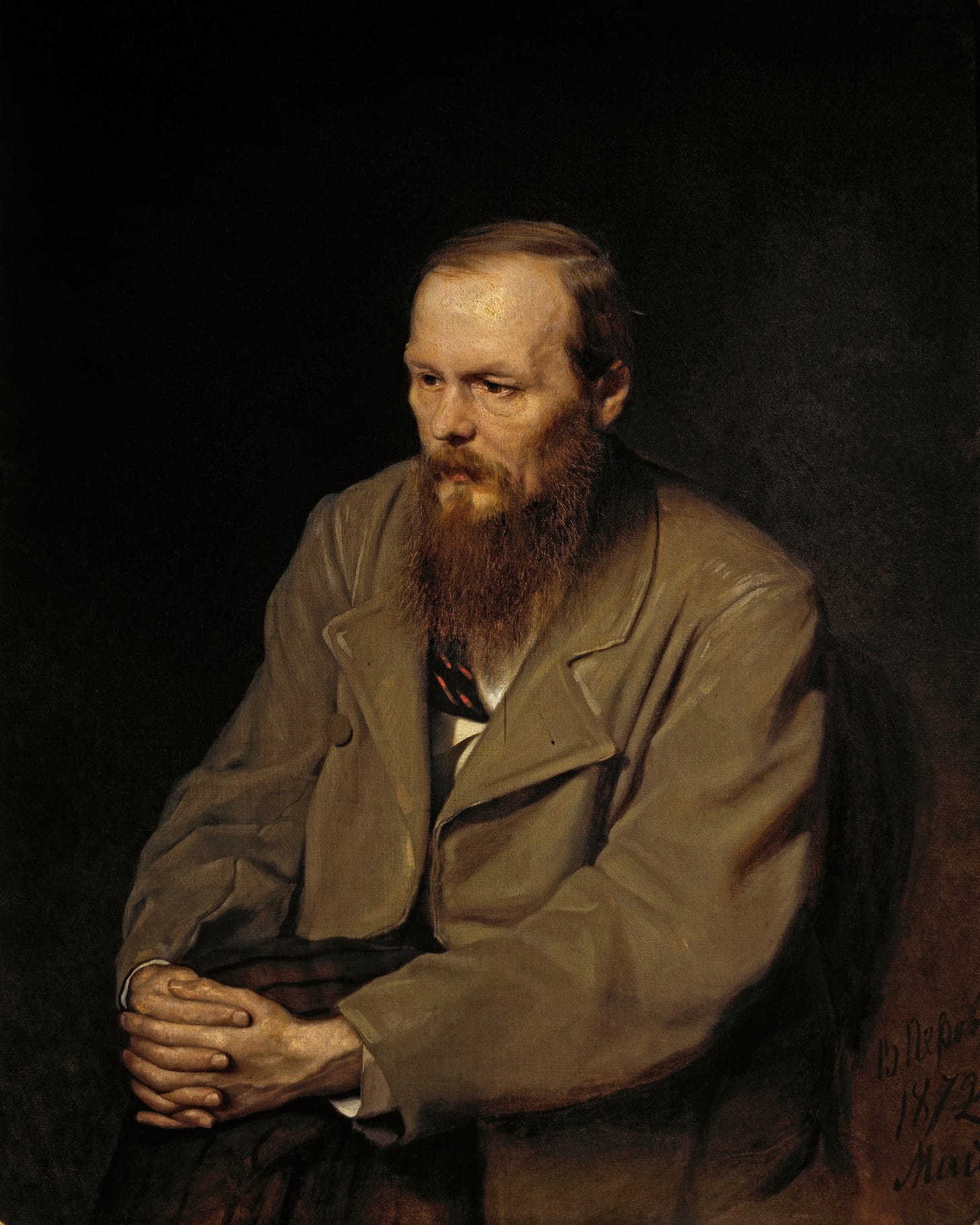

Dostoevsky was a master writer, and even more, he was a true genius of the human psyche. He was also a devout Orthodox Christian. So why did he choose to cast questions over the holiness of his most holy character? And why must Alyosha go through this on his hero’s journey?

These are the questions that have plagued me since finishing this book last year. What is Dostoevsky trying to tell us?

If he wanted to promote faith, surely it would’ve been easier to cap off his account of Elder Zosima with an incorrupt body. Perhaps a miracle or two at the grave.

Instead we get this.

The easy answer would be that Dostoevsky wants to be a voice of reform in the church, tearing down superstition in favor of a more rational faith.

This isn’t entirely without merit. In the voice of the narrator, we are told, “I will add, speaking for myself personally, that I find it almost repulsive to recall this frivolous and tempting occurrence, essentially quite insignificant and natural.”5 Clearly the narrator has a simple answer for the smell of Elder Zosima’s body: that’s what naturally happens.

And yet, this answer seems a bit too easy. The narrator is not an anti-supernatural rationalist. He describes Alyosha as “even more of a realist than the rest of us”6 but that does not keep him from believing in miracles. Furthermore, he recounts the story of other elders who are believed to be incorrupt, and while his language leaves room to doubt whether the narrator believes this in in fact true, we are not told outright that it’s false.

Of course, there is also that ever-present literary question of the extent the author agrees with the narrator. We will not traverse that particular path here.

A more fruitful path, I believe, is seeing this episode for what Father Paissy sees it: a temptation. Immediately prior to the back and forth with Alyosha quoted above, Father Paissy asks, “Have you, too, fallen into temptation?”7

Alyosha is faced with a question: “Do I believe the holiness of the man I experienced in life, or will I allow my expectations overshadow my previous experience?”

In our own ways, all of us will face this question. Confronted with unmet expectations, do we revise our past experiences or question what we hoped for? When God doesn’t answer the prayer you wanted most, did he really answer the ones from the past? When the friend fails to show, were they ever truly worthy of the title? When the pastor falls, was the faith he gave you real?

The list could go on.

I don’t know all the reasons Dostoevsky chose this for Alyosha. Maybe it really was just a critique of superstition.

But I think there’s more.

I think there’s a deeper truth here that as we live the life of faith we will undoubtedly face moments in which the way we expect God to show up isn’t the way that he does and we begin to doubt the past because of the unforeseen present.

This wasn’t the last trial Alyosha faced.

The book ends in a scene that I can only imagine would’ve ripped Dostoevsky’s heart out to write. It is the funeral of a young boy. In 1868 Dostoesvky lost a three month old baby of his own, and it deeply affected him. It was a tragedy for which he wouldn’t get answers. Tragedy’s are like that, it’s the lack of answers that make them fully what they are.

When Alyosha gives a speech at this funeral, he is no longer a man building his faith on future expectations but is firmly rooting all of life in the power of memory, of the sweetness of the past. He tells the young boys assembled before him:

“You must know that there is nothing higher, or stronger, or sounder, or more useful afterwards in life, than some good memory … If a man stores up many such memories to take into life, then he is saved for his whole life. And even if only one good memory remains with us in our hearts, that alone may serve some day for our salvation.”8

I like to imagine that Alyosha, as he went on his way through life remembered not the odor of corruption but the love of Elder Zosima.

Dostoevsky may in fact be challenging us all to that sacred act of remembering the good, the true, and the beautiful even when life brings evil, lies, and ugliness.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, (New York: Picador, 1990), 350.

19.

29.

349.

26.

821.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1-Yf5nIvt8N6nxJbmb7GOoO3JHGv8yuP9/edit?usp=drivesdk&ouid=117876598294722994295&rtpof=true&sd=true

Hey Austin, I wrote my Master's "Thesis" on this very topic. You might enjoy a deeper dive into what you've already found!

Beautifully written as always. I also did not understand the book when I first read it, yet Alyosha’s doubt throughout this scene and in his conversation with Ivan really captivated me. I hope I can understand it better the next time I re-read this masterpiece.